Mirka Meyer | Visual Communication and Branding Specialist

Mirka Meyer started her career in 1995 as a graphic designer in New York. She has since built up a successful career as a communication and branding specialist for various corporations and agencies in New York, Los Angeles and Frankfurt. In 2002 she came to Berlin with Pentagram and shortly thereafter co-founded the branding agency ‘metorical’ as well as the gaming magazine [ple:]. In 2008 she redirected her professional career from the creative industries to the humanitarian sector, managing acute and chronic emergencies with Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF / Doctors without Borders) in the Central African Republic, Ethiopia, Haiti, Chad, DR Congo and South Sudan. Her current project brings her knowledge of visual communication together with the pressing practical communication needs of humanitarian emergencies in developing countries. Mirka received her BFA from Art Center College of Design in the year 2000, and currently lives in Nairobi, Kenya.

When people see my CV nowadays I usually get a few puzzled looks and definitely a few questions. It is neither the most common, nor the most obvious path that I have taken. But I have always strongly believed in “thinking outside the box.” I know that this belief has given me a very unique view of the world and very valuable insights into the importance of visual communication within the context of humanitarian emergencies.

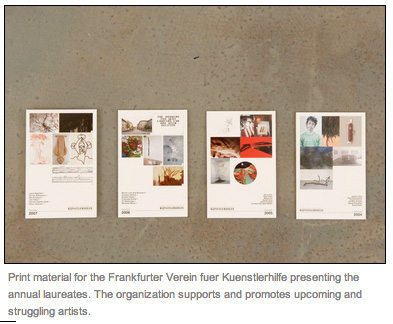

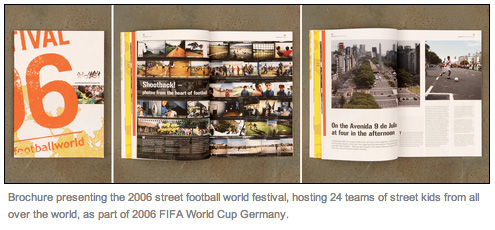

After graduating from Art Center in 2000, I returned to Germany where I co-founded metorical, a branding and communication agency, that quickly started gravitating towards the non-profit sector. Metorical created branding and visual communication strategies for local and international NGOs such as the Frankfurter Verein fuer Kuenstlerhilfe and “streetfootballworld.” The possibilities and potential of international work sparked an interest in me to get off the computer and go out into the world to experience it myself.

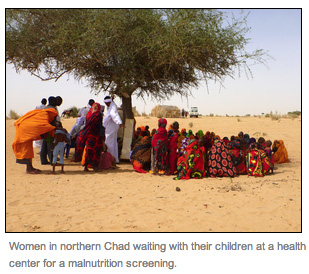

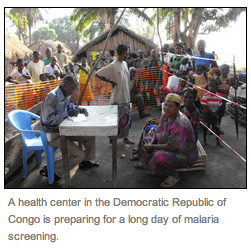

I have since been working for Médecins Sans Frontières as a logistician and project manager treating Malnutrition in Chad, Cholera in Haiti, Kala Azar in Ethiopia, HIV and Tuberculosis in the Central African Republic, Malaria in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Hepatitis B in South-Sudan. As different as these operational and cultural contexts are, they all bare a common thread: The importance of visual communication in multicultural, multilingual and low-literacy contexts, and the operational challenges that organizations face when adequate tools and processes are lacking.

There are many stakeholders that take part in the emergency response to a humanitarian crisis. There are international and national NGOs, UN actors, private companies, religious organizations, national and local governments as well as the population itself that all work alongside and hopefully hand in hand in order to aid the people in need.

There are numerous communication challenges within the process, both internally and externally. Most organizations operate with both an international and national staff, each coming from different cultural backgrounds and speaking different mother tongues. Each organization arrives with unique expertise and operational policies and tools, which are often based on first-world management standards. They are often highly technical but are implemented in a third-world context, which often has low education and literacy levels.

Aid delivered to populations in crisis meets many communication challenges. Not only must specific emergency needs be met quickly, but the organization itself is also faced with presenting their mission, goals and processes to the local population. Communication structures that work both upstream and downstream are essential to the success of any humanitarian mission, and require that the local population itself is carefully regarded and included in the communication. If they are listened to and given a voice, the rate of success is much higher.

The channels of communication are complex and often fraught with misunderstandings and obstacles. Finding a common language and establishing open and transparent communication channels in a hectic emergency setting is a well-known challenge for all of us.

Fighting malnutrition in Chad, we were working with children under the age of 5. The area was vast with health centers far from away from each other. A lot of time was spent explaining to people why we were there. It was difficult through cultural and language barriers to communicate what we needed from them, finding out what they wanted from us while educating them on what malnutrition was and what they could do to save their children.

What if, there were visual communication materials that explained what malnutrition is, where it comes from and what mothers should and shouldn’t do to help their children? One communication kit that could be used worldwide with adaptations depending on the cultural context!

During the end of our intervention in the Democratic Republic of Congo we decided to distribute cholera and malaria kits to the districts health centers as a preventative measure for the next seasonal outbreak. Cholera kits contain chlorine for the production of safe drinking water and disinfection, medications for the first patients at the onset of the epidemic and key tools needed to set up a basic treatment site.

What if, we had specifically designed donation kits that facilitate the mixing of chlorine solution and standardized administration of medication? Including a visual guide containing the key steps and processes? One single kit that can be used worldwide!

One day in South-Sudan I entered the logistics warehouse and I found a team of daily workers putting together a bookshelf based on the visual construction manual of our favorite western-world Swedish furniture manufacturer. To my own surprise, a group of proud men, being unable to read, while not speaking the same language were able to mount this piece of furniture on their own. And not only did they succeed, but they were having fun, bonding over the challenge and their achievements.

What if standardized operational processes, such as maintenance processes of standardized technical equipment or basic medical procedures, could be presented as a visual manual? One single format that can be used worldwide!

As I always knew to be true: Once a designer, always a designer. By going as far away from my creative roots as I thought possible, I realized I had arrived in a situation with infinite communication challenges and a strong need for process and product innovation. As a result, the idea was born, to take the already existing area of Communication for Development (C4D) one step further, or maybe two.

How can design help bridge the gap between various parts of an organization and its urgent mission? Can an engaged visual platform link together employees from around the world, local support staff and the direct population in need to bring relief more efficiently? And ultimately, how can design thinking empower local staff and the target population, tapping into their experience and vast knowledge for long-term results?

I am certainly not the first to ask these questions. But I am one of the few branding and communication specialists that has worked and lived in close proximity with communities in severe crisis and worked with national staff with incredible expertise to offer. Visual communication as well as product and process innovation bares so much potential in streamlining the humanitarian aid process. But this can only be achieved if local knowledge is incorporated into the development process. In creating this communication platform, I am inviting everybody to join. We aim to transform every day challenges into motivational tools, and communication gaps into a wealth of information in order to facilitate the delivery of aid to the populations most in need.

Read the original post on Art Center’s Dotted Line blog.